I wasn’t able to write a new post this week, but did revisit a post that I wrote last fall, which in some ways serves as a continuation of a theme I gravitate toward: the connections between history and technology.

As many of you know, I’ve found the work of Venkatesh Rao to be fascinating and influential.

His writing explores and explains a world that is being eaten by software (see his excellent ebook Breaking Smart).

I don’t know if he’d agree with this, but to me, he is a student of large transitions and the collisions that ensue as cultures adopt new technologies.

What I enjoy so much about his writing are the connections he draws between longer historical cycles and and the present history we’re living through. The first work of Rao’s that I stumbled on was an essay in Aeon from 2013 titled, “The American Cloud.”

The below post attempts to synthesize that essay — an essay that imagines the Hamiltonian vs. Jeffersonian versions of America through the lens of the Cloud/App technology cycle that characterizes much of post-modern life.

Summary of what this post will cover:

During their lifetimes, Jefferson and Hamilton promoted very different visions for what America could and should become.

Their disciples have carried those competing visions through the generations, and their contest remains central to the American experience of the 21st century.

Hamilton’s America largely played out in practice, but Jefferson’s America persisted and has served to obscure Hamilton’s vision from view.

The cloud (referring to software), consists of infrastructural platforms (e.g. Salesforce or Shopify), on top of which an ecosystem of applications are developed (e.g. Pardot or Shogun).

The United States that many of us know and feel reflects Jefferson’s vision. It resembles the application layer and takes the form of nostalgic theaters of consumption (e.g. Whole Foods & Starbucks).

The United States that many of us do not know, feel, or see reflects Hamilton’s vision. It resembles the infrastructural layer and takes the form of large-scale production facilities that serve as the invisible, industrial back-end.

Exploring The American Cloud

To open, Rao asks us to imagine the cultivated experience of every Whole Foods. It is as through we’ve entered a bucolic, hyper-local farmer’s market. But the marketed veneer is just that, a thin veiling of distant industrial realities that we seek to obscure in the cultural spaces of our consumption.

For Rao, the modern system of retail was the first piece of what he came to understand as the American Cloud, “the vast industrial back end of our lives that we access via a theatre of manufactured experiences.”

The origins of this America can be understood through America’s original conflict with itself, the eternal debate between Hamilton and Jefferson for the soul of America.

Would America be an industrial nation with a strong central government, or would it be a republic of small farmers?

It was Hamilton’s vision of the American System that ultimately catalyzed the emergence of the American cloud, though it would take nearly 150 years — from the Civil War to the emergence of the internet — before the American System would be fully obscured from view.

In the meantime, Rao writes, “small farms would give way to transcontinental railroads, giant dams, Standard Oil and US Steel.” Meanwhile, the most consequential political activity — the “in the room where it happens” activity — retreated into institutions that few ordinary citizens could understand or access.

Hamilton’s vision won out of course. Rao writes, “Over the course of two centuries, the Hamiltonian makeover turned the isolationist small-farmer America of Jefferson’s dreams into the epicenter of the technology-driven, planet-hacking project that we call globalization.”

Rao refers to the signs of this makeover as Hamiltonian Cathedrals. These cathedrals “emptied out and transformed the interior of America into a technology-dominated space… and have been so psychologically disruptive that the bulk of America’s cultural resources have been devoted to obscuring the realities of the cloud with simpler more emotionally satisfying illusions.”

What does he mean by “cultural resources devoted to obscuring the realities of the cloud with simpler…illusions?”

This is where Rao turns to an important observation of the day to day American experience. Though Hamilton’s industrial America replaced an agrarian republic of small farmers, Jefferson’s vision appropriated a new approach to remain relevant. Finding it impossible to prevent the wave of Hamiltonian industrialism, perhaps the best way to compete would be to obscure that reality from view; to make it invisible in the lived experiences of the majority of the population.

How to create these illusions? How to obscure industrialism and infrastructural back-ends?

Rao refers to these illusions as Jeffersonian bazaars — theaters of consumer lifestyle inspired by Jefferson’s nostalgic vision of a bucolic pre-industrial life. Rao writes, “This theatre can be found today inside every Whole Foods, Starbucks, and mall in America… Structurally then, the American cloud is an assemblage of interconnected Hamiltonian cathedrals, artfully concealed behind a Jeffersonian bazaar.”

Though the thin veil between Hamilton’s America and the bazaars of our daily lives is easily pierced, few Americans interact with the Hamiltonian cathedrals. Rather than interact viscerally with the feed lots and the supertankers, we interact with Hamilton’s America via “two distinct interfaces.”

Interface # 1

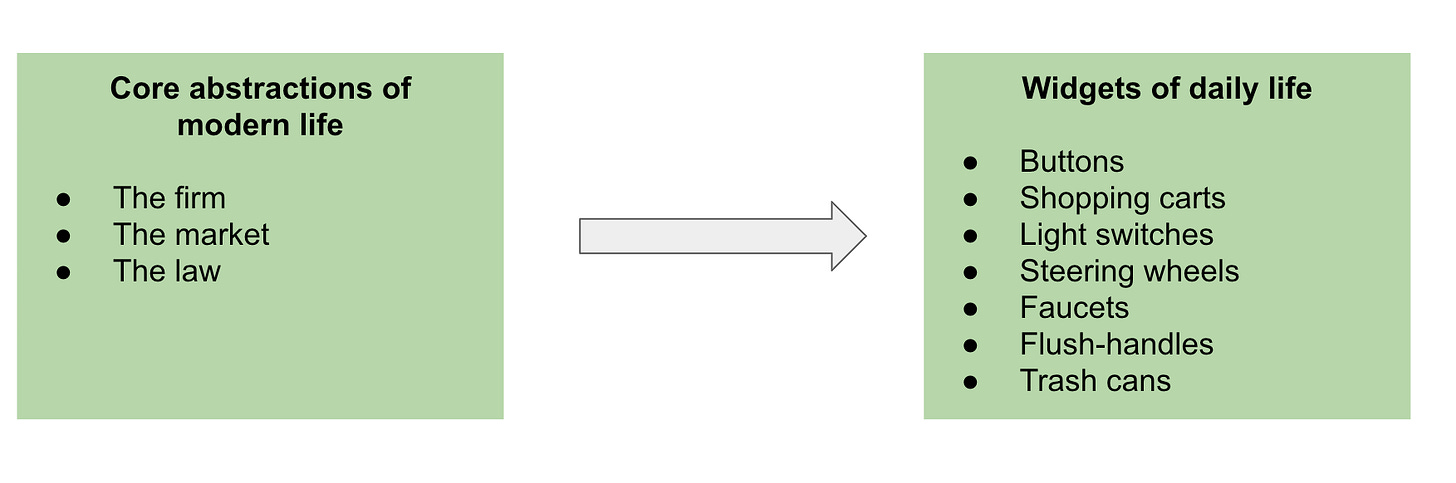

The first interface is Ronald Coase’s core abstractions of modern life and their mediating objects.

The abstractions of modern life are three-fold: the firm, the market, the law. These abstractions are mediated by a variety of instruments: dollars, votes, contracts, etc.

Interface # 2

The second interface consists of the widgets of everyday life, which Rao writes, “connect us to the Hamiltonian cathedrals themselves.”

Critique or Observation?

So is Rao simply making an interesting connection between America’s founding conflict and the cloud/app-driven digital world that has materialized?

Or, is he offering a critique of America?

Rao plays the part of Tocqueville, more than the part of Siskel & Ebert. He is observing America through an interdisciplinary weave, and though within the observations and metaphors are elements of critique, they are effectively delicate.

For example, he argues that in our intentional obscuring of the heartland’s Hamiltonian Cathedrals, by way of the cultural and romantic spaces of the Jeffersonian bazaars, “we strive to render technology invisible to our appreciative senses, while retaining its instrumental capacities…allowing us to have our technological cake and eat it, too.”

And again when he writes, “And so this is how we inhabit the American cloud in the modern age. We finance the Jeffersonian consumption of our evenings and weekends through participation in Hamiltonian production models during our weekdays.”

His point? That in the chaos of progress and innovation, we have created artifice.

But for Rao, is that a bad thing? Is it good? Is it neutral? What should we make of it?

My impression is that Rao is mostly an observer, appreciating all that he encounters with mindfulness, not judgement. He writes, “My own perspective is something like an ironic religion of technological mindfulness, one whose central perceptual act is the projection of a cryptic agency onto the whole that is neither malevolent, nor benevolent, but merely to be decrypted.”

What is he saying here? That his work is merely an attempt to decrypt and understand. Not to celebrate or condemn. His is a pilgrimage into the metaphorical and metaphysical piping of the American system and all its juxtapositions.

Interesting to read this in light of the rise of e-commerce and the increasing importance of digital experiences - whil the experience of online shopping is somewhat curated, there’s no way amazon.com resembles anything like a bucolic Jeffersonian ideal!